La página que intenta visitar sólo está disponible en inglés. ¡Disculpa!

The page you are about to visit is currently only available in English. Sorry!

A few minutes before dawn biologist David Logue pulls the car off a narrow road near the top of a mountain not far from Mayagüez, Puerto Rico, where he is assistant professor at the University of Puerto Rico. The rim of the sun is barely visible on the horizon. Prime time for birdsong.

David and his graduate student Daniel Pereira immediately begin to offload sound gear. We will use it to lure a tiny endangered songbird and tempt it begin singing, to initiate a duet with its mate. The elfin-woods warbler is little studied, but one known fact about it is that it sings duets.

Duetting is the tightly synchronized sharing of song by male and female birds, and for scientists, one of the most baffling of birdsong forms. It is relatively rare. Although more than 400 birds are known to duet, this number accounts for only about 4 percent of bird species. Interestingly, though, the birds that duet are spread across a large number of families.

David has been obsessed by bird duets since his first day in graduate school at Colorado State University. “There was something very appealing about duetting,” David told me. “It was a very mysterious phenomenon that hadn’t been studied very much. Nobody knew why birds coordinated their singing this way, and it was just so elegant and beautiful—I mean, it’s couples singing together.”

[audioplayer:31701|align:left|caption:]

His new subjects are very different types of birds with very different voices. Both birds live only in Puerto Rico, both are rare. One is listed as vulnerable, and one is hovering at the brink of extinction. The elfin-woods warbler is a tiny black-and-white bird that has been thought until quite recently to inhabit only the highest altitudes on the island, and the brilliant green Puerto Rican parrot is a larger, heavy bird that leads its loud, scrappy existence in the rainforests nestled low among the mountains. The primary threats to both birds’ survival are the confinement of their populations to an island and their low numbers––once an animal become scarce, the odds against each individual are greater and the toll taken by predation, disease, or environmental change is proportionally much more damaging.

The primary threats to both birds’ survival are the confinement of their populations to an island and their low numbers––once an animal become scarce, the odds against each individual are greater and the toll taken by predation, disease, or environmental change is proportionally much more damaging.

The elfin-woods warbler frequents the mountainside just ahead of us, and our trail scrolls up and down through what the Puerto Ricans call the elfin woods, the scrubby trees and vines that take over near the top of the mountain. As we make our way through this sparse growth, birdsong is picking up, and after a few minutes Daniel stops and looks up suddenly, then points to some foliage high above us. I hear a sharp thin note, and when David listens, he says, “Yeah, give it a try.”

Daniel brings out a shotgun microphone and waits for the song to start up again. Then he turns off the microphone and says, “He took off again.”

“Just one bird right now,” David says, still listening and looking into the leaves, tracking something. “There. See him?”

I do. He is a small dark shadow streaking against the early sun. He lands momentarily behind some high leaves and then speeds off again.

“Backlighting is a big problem,” David says about the general problem of finding birds. There is also the fact that most of bird life––the singing, the flight, the sparring, the mating––goes on over our heads.

“Try calling them,” he prompts, and Daniel holds the digital recorder away from his body to broadcast the warbler's song.

But if there are elfin-wood warblers here other than the one that passed us on its way up the mountain, they aren’t paying any attention to the songs Daniel plays back. At about 10 a.m., we are working our way down the mountainside, and the few birds we have been hearing seem to tire of the singing effort.

Across most of North America and in other temperate climates, birdsong is performed almost exclusively by male birds. The male is the one who has the time and the assignment. His mate of the season is busy laying eggs, brooding, and stuffing the oversize maws of their chicks. Although the male may help with the feeding, his main job is to stand guard over the pair's summer territory, and he sings to ward off any intruders, birds of any kind and predators. Their territory, their pairing, and their family are temporary. The birds initiate all this when they fly north and arrive in their nesting grounds, and they end it when the birds scatter back south. “But here in the Neotropics,” David tells me, “bird families are more stable.” They aren’t nomadic, and for many species, the pairs are more or less permanent. They are monogamous, at least for the social enterprise of raising a family. Because tropical birds aren’t working under time pressure to produce chicks that can travel before their impending migration, the breeding and brooding schedules are more relaxed. The male and female share the work of raising the young, and both the male and female birds sing.

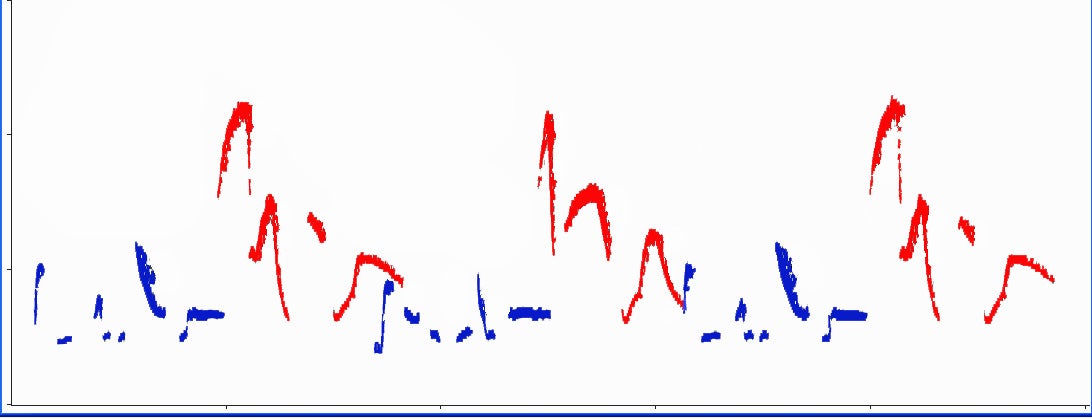

Back at the university we sit at David's computer to listen to the duets of the bird we glimpsed so briefly. The thin, rattle we heard on the mountain is there, and it is seamlessly linked to a brief series of sharp chits. The song sounds as if it comes from one bird.

“It may take some time before we get this in the field.” He says and then clicks on a sound file for a duet he understands thoroughly, the songs of the black-bellied wren. The wren is very shy and elusive, and compared to the truly flamboyant birds in the Canal Zone—the toucan, the flashy parrots, and the bright green but stolid motmot—the black-bellied wren’s coloring is rather dull. It is the size of a large sparrow, and for a little decoration, it has a stippled black pattern below its white bib. Although a whole family of these wrens will often move about together, their coloring and their secretive habits enable even a group of four or five of them to stay out of sight.

What the bird lacks in flash it more than makes up for in song. Both males and females are prodigious singers. They sing in distinct phrases and repeat them. And repeat them. They seem to find it hard to stop. It's endurance singing.

David imitates the typical phrases, making a low little scat song and tying it up at the end with a rising phrase. "Whee-pheew, foh-loddle-loddle-lay. The guidebooks say it sounds like cream-of-wheat. That’s not what I get out of it. But all you have to do is hear it, and you’ll know it.”

True. The male and female wrens are committed to their continual enterprise of song. The male bird sings, the female responds––over and over, without an audible pause between each bird’s part. There is no slice of silence. You have to have very good ears to recognize that there are two singers.

“I think I'm the first person to look at the structure of duets," David says. "Each male bird has probably forty different songs he knows how to sing.” In the bird world, this is a good-sized repertoire but not so prodigious as the number of tunes learned by some of the song sparrows. “But listen, . . .” He re-clicks the same sound file, and says, “A pattern, right? It’s a little different, but there’s still a pattern.”

After he plays a couple of long bouts of these exchanges, he asks “So why do two birds do this duetting thing? How does it help them succeed?” A recent scientific review of duet singers makes clear that the function of a duet probably varies from one species from one species to another. But there are some constants.

Singing is costly. It consumes a bird’s energy and time and it alerts predators to the bird’s presence. But it doesn’t cost the bird as much as actual combat with competitors, and because sound is a very rapid, very effective means of communication, singing is a good substitute for physical contact. Singing or calling can divert an approaching bird intruder or competitor or ward off a predator before an attack becomes necessary. It can mediate disputes and spares the birds and danger and energy of physical assault. It has also been proposed that the strength of singing also helps to attract and guard the female because female birds may equate the amount of energy a male bird puts into singing with the amount of energy he will put into helping her raise their young.

"Most of the work on duets looks at what they do, what function they serve," David explains, "and one of the dominant theories is that they are cooperative territory defense. There’s also been some speculation that this continual singing is a way of staying in touch to prevent either bird from flitting off for a quick mating with another bird. But that’s not my take on it."

He brings up the volume on the wrens' duet. “Listen to how hard she’s working to get it right." There is an anxious obsessive quality to the female’s timing of her entries.

“Why is it so important that she get it right?” David asks another rhetorical question.

When I don’t answer right away, he turns the question around. “What happens if she doesn’t get it right? He attacks,” David winds up his monologue, “because he isn’t convinced she’s the female who is his mate. If she isn’t, he doesn’t want her anywhere near the eggs or chicks he is responsible for—remember, we’re in the tropics, so he is sharing the work of raising the family.”

It’s a dangerous game. The male calls whee-phew, and while his last note is still sounding, the female’s warbling response has to come at exactly the right split-second, on the right part of the beat, and continue in exactly the right yodel, the right sequence of melodic intervals. Otherwise, she could be beat up, and the male could fly off for another, more accurate female.

“It’s like a password,” David says about the strictness of the code. But why would the two wrens need a password? While birds have sound perception that pretty much aligns with our own, their visual capabilities are far sharper than ours. Don't they recognize each other on sight?

All the birds look pretty much alike, he explains, although the males are larger than the females, and in the Neotropics, they are often seeing each other the way we see them, against backlighting or dark foliage. “Remember how hard it was for you to see the elfin-woods warbler this morning?”

It may be hard for the birds, even with their very acute eyesight, to get a good look at each other until they are perching on the same branch. But it is critical to the survival of an animal to be able to recognize its family members, and David believes the coded duet is a means of positive identification, a continuing reassurance that the female bird is the wren’s mate and not some look-alike intruder.

“Do you think it’s the same for the elfin-woods warbler,” I asked, “that there’s something like a code at work?”

“We don’t know enough about that bird yet.”

This is the way that scientists looking at birdlife have to proceed. Bird by bird.

David's second bird-in-the-bush is such a strong contrast to the elfin-woods warbler that it seems an improbable singer of duets, in fact an improbable singer of any kind. This bird-in-the-bush is much closer to hand for David than the elfin-woods warbler because its only populations are captive. He can find them any time.

To have a look at the Puerto Rican parrot, we drive around the western edge of the island and turn south for about thirty miles into the heart of Karst country, where the shoulders of lumpy limestone mountains hunch up through rainforest. We take a tiny road that follows the channel carved by of the Rio Abajo, driving through dense growth in the low moist valley until we come to a locked gate. The bird’s extremely fragile hold on existence is the reason that the José L. Vivaldi Aviary is closed to outsiders.

Native to Puerto Rico and confined to the island, the parrot is a loud-colored, aggressive bird with a typically raucous parrot voice. In spite of these pugnacious characteristics, the parrot is nearly extinct. It numbers fewer than a hundred, and this figure is up from its low of thirteen birds in 1975. The government is involved in a concerted captive breeding program at two sites, one on the eastern end of the island, El Yunque National Forest, and this one in Rio Abajo State Forest.

A young Puerto Rican man meets us to open the gate. Brian Ramos Güivas, another of David's graduate students, has worked at this compound for more than ten years, and he knows the Puerto Rican parrot as well as anyone in the world.

Brian shows us two parrots in a large stand-alone cage, where he begins his customary presentation about the birds and their progress away from extinction. The two birds are a brilliant green and roughly the size of a crow if you don’t consider the crow’s tail. Brian points out a brief bold band of bright red where the heavy, curved beak meets the head and notes that this stripe is more pronounced on male birds than on females. “Also, the eye—inside this white eye ring—“ he indicates the iris—“is yellower in males, and it gets yellower as the parrots get older.”

“Yes, the parrots are aggressive––” he agrees. “Very aggressive. But these two, " he says about the pair eyeing us and sidling a little toward us, "have been hand-raised, maybe because they were sick or needed some kind of extra care, and they don’t show aggressiveness because they’re not afraid––which is not good for the birds that will be reintroduced to the wild.”

The program at the aviary is an intensive operation to replicate the bird’s natural reproductive pattern. It begins with collecting eggs from nesting pairs, incubating them, raising the chicks without providing evidence of the fact that their caretakers are human beings, moving them to a special evacuation building when hurricanes blow over the island, and then, before release, training them to recognize and avoid their predators. In addition to the inefficient foraging and homemaking skills of newly released birds, two innate factors limit the rebound in the parrots' numbers: the birds' aggression toward prospective mates and their apparent inability to take care of more than two chicks. But Brian reports that the staff releases about thirty birds a year, and that losses of newly released parrots are diminishing every year.

The two ogling us from their perch haven’t made a peep. But we can hear plenty of squawking from a wooded area behind the largest building in the compound, and when we approach the flight cages, cacophony breaks out. If one parrot’s squawk is loud, ten parrots in full voice are ear-shattering.

David comes over to explain that very little is known about how parrots live in the wild. Given that they are so brightly colored and blatant with their voices, this surprises me. But he says that, like the elfin-woods warbler, they are difficult to see. They live in very dense foliage and are almost always observed with backlighting. Most of what we know about parrots we have learned from captive birds, and in spite of how much we know about their mimicry, we know very little about the vocalizing of parrots living in the wild.

Most parrots live what is called a fission-fusion lifestyle. Every morning, the flock leaves a common roost where the birds have spent the night, and they fly off to forage, separating into smaller groups until late in the day, when they gather closer together. As they try to decide on a new roost for the night, the groups of parrots call back and forth, imitating each other’s calls. It has been proposed that this mimicking is to mediate the reuniting of the two groups separated during the day before they settle on a roosting place in the evening.

“That isn’t duetting,” David explains about the exchanges between groups of birds. “That’s song matching.”

In a top corner of one of the big flight cages hangs a metal cylinder with an opening at the bottom and an enclosed compartment at the top. This simulates the parrots' nesting situation. The birds move into tree holes, preferably vertical cavities because they are less accessible to predators. While housing considerations for their breeding are relatively straightforward, the rest––aggression and song exchange between prospective mates––is not.

Once a pair is made, the parrots are monogamous until one of them disappears for some reason or there is what David calls a “divorce,” when for some reason the couple can’t keep it together to raise another clutch of chicks. The male parrots don’t incubate the eggs, but they do feed the chicks.

“What I want to see,” Brian says about the vocal communication research project he has proposed to David, “is if the duets affect how often the males feed the chicks.” In a row of three contiguous cages, Brian will house a female parrot in the middle cage with a male in the cage on either side of her. He will monitor the amount and format of vocalizing, and then see which male she prefers. Once the female parrot has selected a mate, he will house the two together in a larger crate with a nesting cylinder and wait for the chicks to hatch and the male get to work on the provisioning.

“When the pair starts duetting,” I raise my voice against the ratcheting background of clamoring parrots, “how can you tell the two parts from each other?”

"The females make a slightly different sound, more like crying than squawking,” Brian characterizes it. I wonder how he will ever to able to hear it well enough to distinguish this in this pandemonium?

We drive out of the compound with parrot calls still reverberating in our ears. None of it sounded like singing, and I wonder how a bird can be said to duet without making some attempt at melody or harmony or counterpoint. Or at least some audible indication of compatibility. When we stop for lunch I say, “I wonder what those voices will sound like when they get into a duet.”

David gives me a long glance. “That was a lot of what you were hearing this morning.”

Evidently during all the clamor, he hadn’t thought it necessary to point out the exchanges of raucous sequences between the males and females.

“That was a duet?” All those raucous squawks and brays? But what about all those comparisons to happy monogamy?

“That’s what you were listening to.” Apparently, those unlovely sounds haven’t changed his ideas about pair bonds and biological parallels to the bonds between human couples.

Reprinted with permission from Calls Beyond Our Hearing: Unlocking the Secrets of Animal Voices, by Holly Menino, published by St. Martin's Press © 2012. All rights reserved.