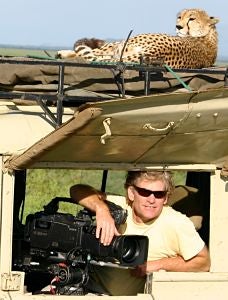

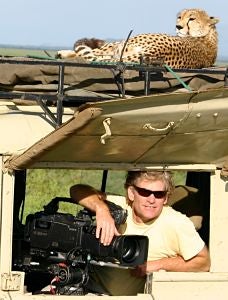

Courtesy of Christopher Palmer

UK born, Christopher Palmer was working for the Audubon Society in the early eighties when an executive VP issued the following directive to the then presiding president, Russ Peterson:

“Russ, we strongly recommend that Chris Palmer be fired.”

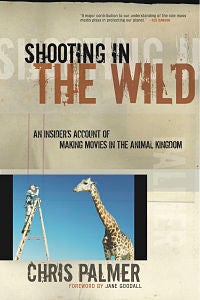

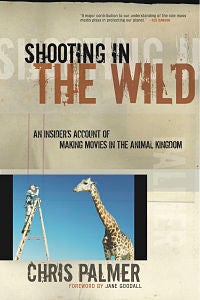

The stern suggestion was the result of Palmer’s relentless pursuit of making the first-ever Audubon documentary, which, rather than a film, only produced contempt amongst his superiors who viewed the venture as too risky. The request for his termination is also the first line of his new book,

Shooting in The Wild: An Insider’s Account to Making Movies in the Animal Kingdon, in which Palmer threads an autobiographical tale of a 30-year career into a foray on the growing but morally bankrupt field of environmental filmmaking.

What made you so driven to produce environmental films early on in your career, so much so that you were willing to risk your job?

When I was working for Audubon I was lobbying. I would spend 5 days preparing testimony on issues like natural gas pricing, solar energy, and nuclear power, then go up on The Hill and stand before half a dozen congressmen and a couple senators and present my findings. After a while of, I began to say to myself, ‘what am I doing? Is this really the best use of my time?’ This was 1982, when there was very little environmental programming on TV. Eventually the seniority at Audubon said ‘okay if you can find the money yourself go ahead.’ By chance I came across one of Ted Turner’s colleagues who said she was looking for environmental programs. I pitched her one, she loved it, and it developed from there.

Why has wildlife based television programming become so popular recently?

Over the last 30 years, very slowly, sometimes imperceptibly slowly, there has been a growing interest in environmental conservation. But the major player is money. Television is a ratings-driven, branding-driven, money-driven, capitalist system. For most of these shows all it takes to make much of what you’re seeing on TV now is a very exciting and charismatic host like a Jeff Corwin or the late Steve Irwin, and in a single afternoon and on a tiny budget you can shoot a pretty exciting half hour show.

Courtesy of Christopher Palmer

What are some of the unethical practices in contemporary environmental programming?

One of my concerns is audience deception. For example, someone watching a wildlife television show at home might see a menacing grizzly bear approach the carcass of an elk and maul it to smithereens. But what a person watching won’t see is that the bear is from a game farm and the innards of the dead elk have been laced with M&Ms. Another one of my biggest concerns is the environmental harassment and destruction that takes place. The other day I saw a segment of the show

Man Vs. Wild on the Discovery Channel. In the clip, the host, Bear Grylls, jumps into a river in order to capture a dangerous lizard. He wrestles with it, which I can tell is staged, eventually pulls this three-and-a-half foot lizard out of the water by its tail, and holds it aloft for the camera, pointing out its sharp claws and elaborating on the ways he could have been harmed by it. Then he takes the lizard by the tail, swings it against a tree, pulls out a knife from his pocket, and plunges it into the back of its neck to kill it. Don’t forget now, this is Animal Planet we’re talking about. It’s amazing that in 2010 this type of cruelty to wild animals is still being used to entertain. In some ways it feels like we’ve gone backwards fifty years.

(For further reading check out our article by Ted Williams on phony wildlife photography that appeared in our 2010 March-April edition)

Given the nature of some wildlife programs, do you think their increasing popularity is detrimental to wildlife conservation?

It’s not so black and white. On the one hand, anything that reminds the general public that they are an integral part of nature, and not apart from nature, is playing a role in furthering the cause of conservation. But on the other hand, you have a lot of these shows presenting wrong messages. Steve Irwin would go around prodding and disrupting wild animals for the sake of entertainment and higher ratings. In fairness to him, if he were here right now, he would say, ‘I am doing this to make people fall in love with reptiles.’ And there is something to that. He got thousands of kids interested in reptiles, when otherwise they may never have cared. There is so much pressure from shareholders placed on network executives to make them money that they will do whatever it takes to attract eyeballs.

Is there any hope that networks will stop airing shows with messages that are counterproductive to the preservation of wildlife?

I do think more and more people are disillusioned by these programs. I got a letter the other day from a mother who said she will no longer let her kids watch Animal Planet. I am a bit skeptical, but if the public can be made to grasp how harmful these shows are, and actually ceases watching them, then the ratings would flip and the networks would have to respond. This is the perfect time to begin having this conversation. Last week Discovery Channel had their annual

Shark Week, which is a week of programming based on the deception that sharks are man-eating and menacing creatures. The network gets the ratings, but the sharks don’t get what they need, which is people who are empathetic to their plight. Their populations are being wiped out for fin soup.

(For further reading check out Christopher Palmer’s editorial in the Huffing Post about Shark Week)

Are there any programs or people that you think are producing valuable environmental films or videos, which adhere to the ethical methods laid out in your book?

One program I like is Planet Earth. The footage is thrilling and from what I can tell is made responsibly. I like

Whale Wars too, it doesn’t deserve an A+ but

Paul Watson is a fascinating character, and it promotes conservation.

Howard and Beverly Hall do wonderful work that is gripping and also very commercially successful.

David Attenborough is another hero of mine.

How do you see your role as a modern day environmental filmmaker?

I started making environmental films because I became disillusioned with the usual methods of creating change within society. When I first approached Ted Turner, I told him that I thought in order to build an audience we had to go beyond the hard science to the social and political impact of environmental issues to show people the ways in which they were connected to the natural world. I haven’t been perfect, and in my book I am candid about my own mistakes. I think that now more than ever, we in the wildlife filmmaking business have to put on our thinking hats and find exciting ways to tell wildlife stories, while using sound principals that will engage, entertain, and educate audiences, and always with the aim of advancing the importance of conservation. My hope is that people will become more skeptical about what they see and begin demanding higher ethical standards.

Courtesy of Sierra Club Books in association

with Counterpoint