La página que intenta visitar sólo está disponible en inglés. ¡Disculpa!

The page you are about to visit is currently only available in English. Sorry!

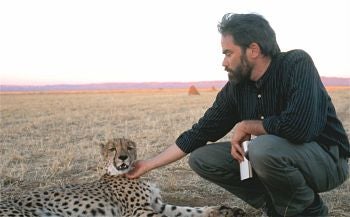

Richard Conniff got blasé about watching animals like cheetahs, because all they did was sit around in the sun grooming themselves.

The following is from "'Swimming with Piranhas at Feeding Time,' by Richard Conniff," a Q&A by Dave Holahan that first appeared April 12, 2009, in The Courant.

Richard Conniff began his writing career in 1969 modestly enough, as a teenager penning obituaries for a small New Jersey newspaper. Later, after college and gainfully unemployed, he pitched a story about the New Jersey "state bird," the salt marsh mosquito, to a local magazine.

It was published, and the rest, as they say, is natural history.

Conniff, of Old Lyme, quickly moved up the journalistic food chain, stalking and writing about larger, sexier and ever more exotic wildlife for magazines such as Smithsonian and National Geographic. He has run with cheetahs in the Serengeti, hung out with leopards in Botswana, even confronted feral thrips and springtails in Hartford's Keney Park, where he helped to identify an astonishing 1,369 species (including a bald eagle) in a frenetic 24-hour "BioBlitz."

He won't demur if asked to track lemurs in Madagascar, where 70 species of the prosimian are. He even took a safari on his own forehead to locate and analyze a thriving population of indigenous follicle mites.

Swimming With Piranhas at Feeding Time: My Life Doing Dumb Stuff With Animals is a collection of 23 of Conniff's magazine articles. His eighth book is an engaging account of his adventures. The author's prose is eminently digestible, leavened with civilized wit and a well-developed sense of irony. Conniff doesn't preach or devolve into scientific arcana as he explores the viciousness of humming birds, or notes that while some politicians behave like monkeys, chimpanzees can wax statesmanlike.

The human characters he cavorts with are interesting animals in their own right. He describes one: "He wore a grimy jacket, held together with bloodstains and duct tape, and a pair of shorts, which revealed that he had scribbled field notes up both legs from knee to cuff."

His title notwithstanding, what Conniff has done, and written about, isn't dumb in the least. The very act of transporting such delicious creatures into our ken makes the reader root harder for their survival in a world stacked against so many of them.

Q: Where are you off to next?

A: I'm not going anywhere right now because I'm trying to write a book that is due in September, so I'm handcuffed to my computer. It's about the discovery of species: who did it, and where they went, and how they died en route, that sort of thing.

Q: Do you have a "bucket list" of species that you want to see and write about?

A: I don't, actually. I tend to like things that are weird one way or another. I often write about things that are a little bit disgusting, like the life you can find on the human body. I also write about beautiful things like cheetahs, and I love going out and seeing what they do. I had one great day in the course of writing this book where I saw six kills. So that was exciting.

Q: When were you most afraid in the bush?

A: There was a time when I did what seemed like a dumb thing. I got out of the vehicle and sat down with a pack of African wild dogs. They have a reputation for ripping people to shreds. But the biologist I was with had been studying these animals for years, and knew them, and he said "See for yourself, try it." So I did. They came around and sniffed the back of my neck. And they did not eat me. My sons were with me, they were 12 and 14 then, and they were watching. I think they were rooting for the dogs. It lasted maybe 10 minutes. The wild dogs walked away. They thought I was boring.

Q: The diversity of life on Earth is truly remarkable. As you note, slews of new species are discovered every year, even as others march toward extinction. What do you make of this?

A: It's a wonderful riot of life forms, and they are also incredibly bizarre. They are surprising to us because our ideas about them are so often mistaken. For example, we think that piranhas are deranged killers, and we view hummingbirds as pretty little sweethearts. It is pretty much the opposite. The piranhas that I swam with in a Dallas aquarium fled from me and hid in the corner of the tank. Hummingbirds are incredibly aggressive. They'll fight and knock each other to the ground. They're driven by their incredible metabolism. The great number of species in general is a function of the need to survive in varied environments and sexual selection.

Q: You also write about wildlife that is close to home. Have you ever noticed how few people see, or hear, or know anything about the creatures that are in plain view, such as the hawk soaring overhead or a bluebird sitting on a fence post by the roadside?

A: I did a story in Hartford, in Keney Park, where biologists identified more than 1,300 species there in a single day, and most people walking through that park would think there is nothing going on here. It is sad that people don't look, because there is good stuff happening all around. Predation and sexual displays are going on in your backyard all the time.

Q: You don't preach in your articles. Here's your chance. Are we irretrievably despoiling the planet?

A: I don't preach because I want people to have fun and enjoy this stuff. If they enjoy it and see how good it is to have these creatures around, then they will care more. That's the best way to get people to avoid despoiling the planet. It's better to say, "Look at this crazy creature, and how it lives, and how much fun it is to have it there. How could you destroy that?"

Q: Is eco-tourism a substantive tool to help save endangered animals and habitat?

A: It definitely is. In Madagascar, there's a national park that had been created by an American biologist where 15 species of lemurs live. If you get tourists coming and spending money, then the local people are less likely to want to cut down the forest and make bush meat out of the lemurs. They see how valuable the forest is. They ultimately want the forest, too. They don't want to turn their country into a desert.

Q: Having seen so much wildlife and wilderness, do you ever get blasé about it? I believe it's called the "if I a see another ring-tailed lemur I'm going to scream" syndrome."

A: One time I got blasé, or frustrated was watching cheetahs. When you go out and write about these big sexy predators, people want to see, or read about them killing. So I spent two week watching cheetahs sitting around in the sun grooming each other. I got so frustrated because it's hard to describe that and make it interesting.

See the original article here.