La página que intenta visitar sólo está disponible en inglés. ¡Disculpa!

The page you are about to visit is currently only available in English. Sorry!

In November 1962 85-year old Rosalie Edge shut down the diminutive office of her once mighty Emergency Conservation Committee at 734 Lexington Avenue in New York City. Documents from more than 30 years of her preservation campaigns filled more than four boxes, which she mailed to the Denver Public Library. Edge died four days later.

Rosalie Edge at the ECC office in 1959. Photo by Carsten Lien.

In Denver her papers became one of the cornerstones of the Western History Conservation Collection, the first archive of its kind.

Before I showed up at the Western History reading room in 1990, few researchers had viewed the 54 files of “items relating to Rosalie Edge’s drive for reform against the leaders of the National Audubon Society,” or files on what Edge’s ECC did to preserve Yosemite, or establish Olympic and Kings Canyon National Parks. On the DPL’s Western History floor a vast painting of Rocky Mountain National Park by Albert Bierstadt brooded. The reading room was like an ancient forest, its silence a contrast to the rackety times in the carpools I drove.

Denver Public Library at Night. Photo by Rhoda Pollack.

In archival sanctums pens and notebooks are as welcome as fresh fruits and vegetables at the U.S. border. I locked up my preferred writing tools and was given a stubby yellow pencil and single sheet of paper. Long strips of stiff paper were the other essential implements issued. I was instructed to raise one like a flag in front of each paper to let Conservation Collection staff know which pages to photocopy, at a cost to me of twenty-five cents apiece. Pre-laptop, taking notes by hand with those little pencils caused cramp quickly. That was ok because it kept me from staying too long, and mother-duty as well as paid work in freelance writing were based at our home in Evergreen, almost an hour away. I had not yet come into possession of Edge’s suitcase or its secrets, so the only primary records of Edge’s existence—in the whole world, for all I knew—were in the Conservation Collection. At the rate I was reading it would take years to go through Edge’s few thousand pages of letters, articles, ECC leaflets, and transcripts.

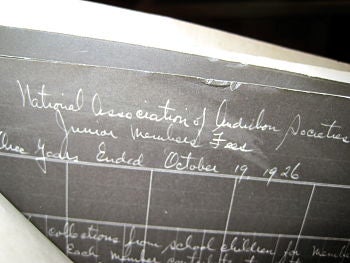

The transcripts recounted boisterous annual meetings of the National Association of Audubon Societies in the early 1930s, and statements taken in a suit Edge had filed against Audubon leaders. File 22 held a photostat of the prized Audubon mailing list she won in the legal wrangle, and which she used to notify 11,000 Audubon members of organizational inertia, or worse. The “Proxies A-Z” file contained votes sent to her by members supporting her insurgency against Audubon’s board. In other files handwritten notes and letters typed on crackly onion skin denounced and praised her, A-Z. A Mr. Wiley criticized her for having been a suffragist, and cast aspersions on her marital state. Other correspondents asked her: Who are you to be doing what you are doing?

A suffragist rumored to be in dubious domestic circumstances was an enticing clue.

Next time: I meet Peter Edge.