La página que intenta visitar sólo está disponible en inglés. ¡Disculpa!

The page you are about to visit is currently only available in English. Sorry!

As Peter Edge surmised, it was not terribly inconvenient for me to drop by the Woodlawn Cemetery in Newburgh, New York to visit his mother’s grave on the way to the shabby-chic bungalow colony in the Catskills where my grandmother summered. Nor was it such an unusual detour for my family. Previous vacations included visitations to many final resting places, including Doc Holliday’s (Glenwood Springs, Colorado) Edgar Allan Poe’s (Baltimore) and of course, those of thousands of Union and Confederate soldiers (Gettysburg). At Woodlawn I studied Rosalie Edge’s headstone and the others in the Barrow family plot until my kids and husband couldn’t take the muggy heat.

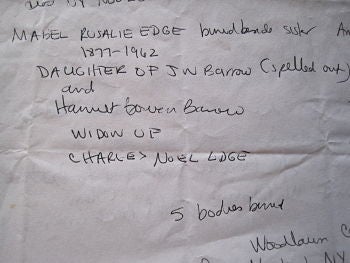

Notes from Woodlawn Cemetery

Grandma Madeline was anticipating our arrival at the bungalow colony with her spry entourage. Visits by descendants sent a wave of excitement through all the residents: Mildred, Annie, Sophie, Molly, Anna and Grandma, women in their 80s and 90s, practically scampered off the porch to greet us, their gab drifting between English and Yiddish. Each of the women had outlived at least one husband. There were no men on the premises; late at night the ladies waltzed and fox-trotted with one another in the club room, after poker.

“Widow of Charles Noel Edge” was how Mabel Rosalie Edge was inscribed for eternity, I had learned from the visit to the Newburgh cemetery. I had not read this on a gravestone before. A few years later when my grandmother was laid to rest beside her husband David, her headstone would not proclaim her his widow. I doubt her bungalow neighbors were inscribed that way either. In 1962 Rosalie was buried near the impressive monuments of her parents John Wylie Barrow and Harriet Bowen Barrow, and her newborn son Hall Travers. But her husband Charles’s grave was not there.

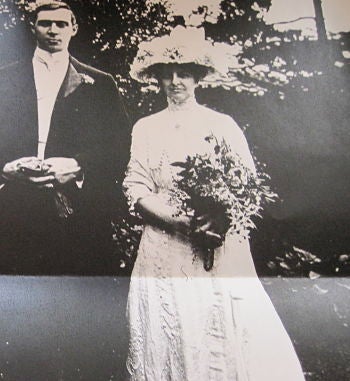

A large photo of Charles and Rosalie on their wedding day in 1909 stood on the piano in Peter’s study.  He told me in our first meeting that despite insinuations I read in letters from Audubon members in the Denver Public Library, his parents never divorced. He said little more than that about their marriage, however. I repeated to Peter that his mother’s conservation papers revealed nothing about her personal motivations for suddenly, at the age of 52, making herself the nation’s leading conservation crusader. Perhaps there were other letters? The gravestone’s curious inscription pointed me in an intriguing direction, I said. I asked Peter whether his mother had specified the inscription and he asserted he had satisfied her dying wish. So what did she mean? He steepled his hands, and leaned in very close to me before speaking in a low growl. “My mother wanted to pursue my father beyond the grave,” he said. The declaration seemed to take a great deal out of him. He got up and went out of the room.

He told me in our first meeting that despite insinuations I read in letters from Audubon members in the Denver Public Library, his parents never divorced. He said little more than that about their marriage, however. I repeated to Peter that his mother’s conservation papers revealed nothing about her personal motivations for suddenly, at the age of 52, making herself the nation’s leading conservation crusader. Perhaps there were other letters? The gravestone’s curious inscription pointed me in an intriguing direction, I said. I asked Peter whether his mother had specified the inscription and he asserted he had satisfied her dying wish. So what did she mean? He steepled his hands, and leaned in very close to me before speaking in a low growl. “My mother wanted to pursue my father beyond the grave,” he said. The declaration seemed to take a great deal out of him. He got up and went out of the room.  He brought back The Suitcase.

He brought back The Suitcase.

Next Time: Peter’s instructions to me.